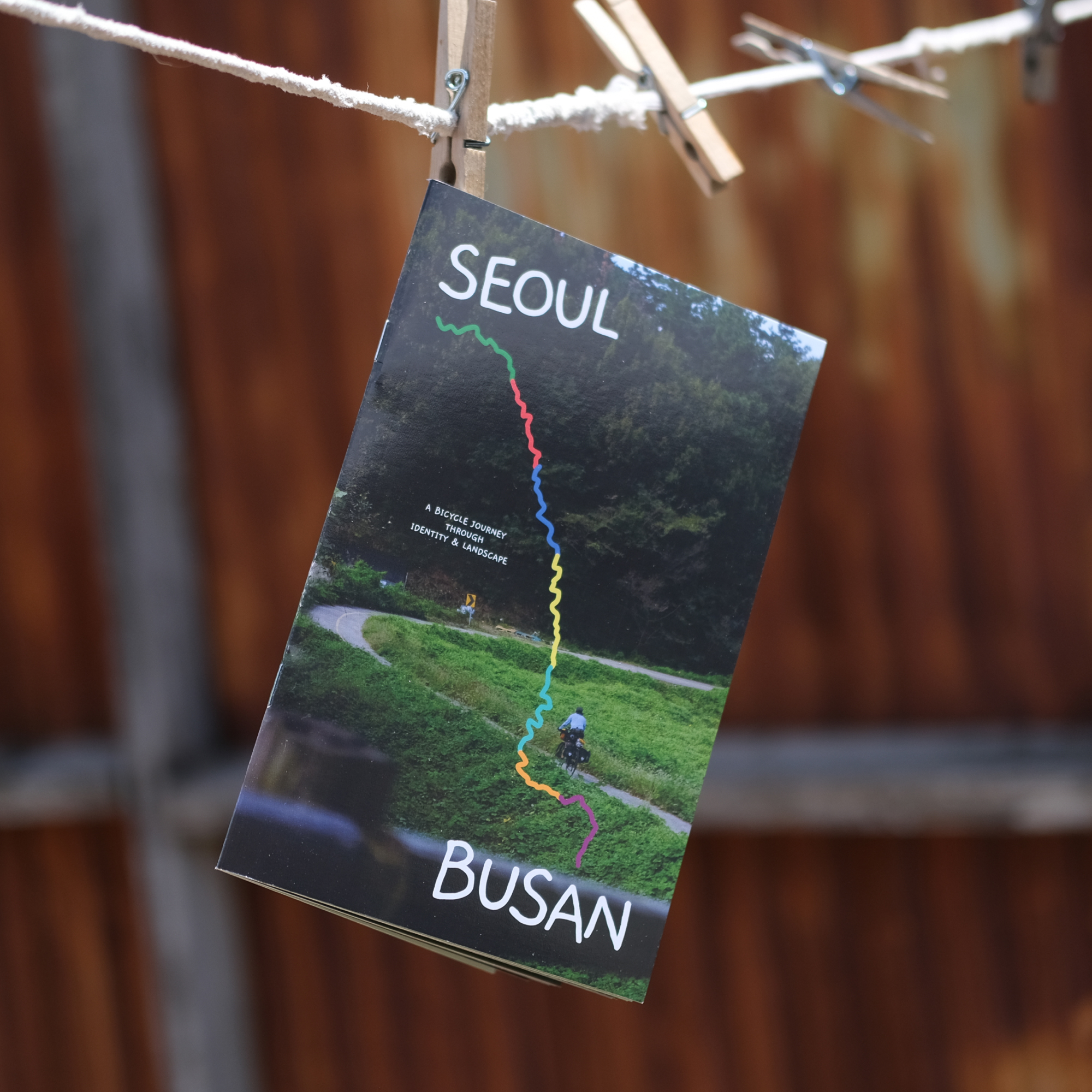

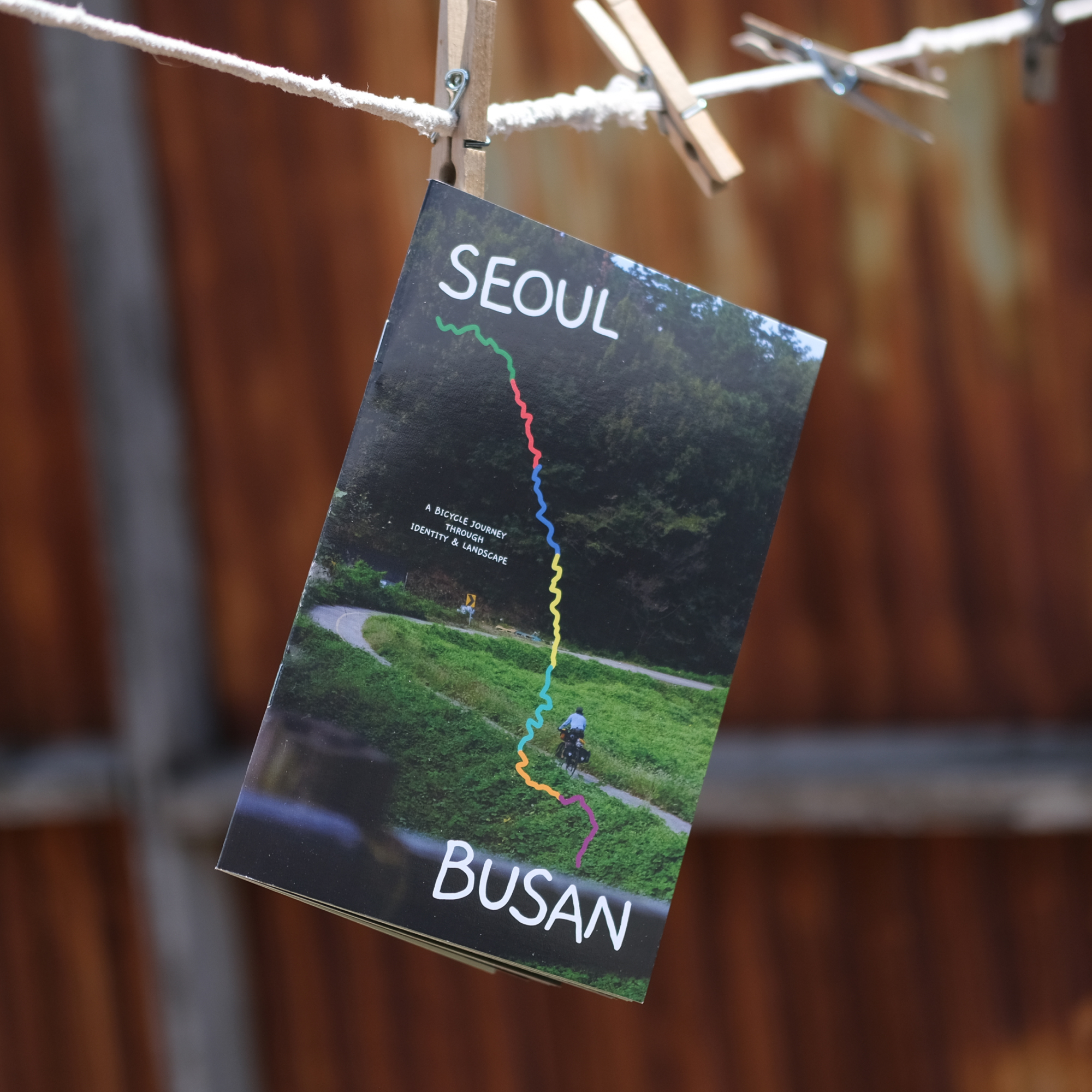

Molly Sugar shares excerpts from her Seoul to Busan zine, chronicling her bike tour through her motherland as an adoptee. She provides insight into her reconnection with her homeland and some tips on traveling by bike in Korea. If you’ve ever been curious to tour in Korea, keep reading!

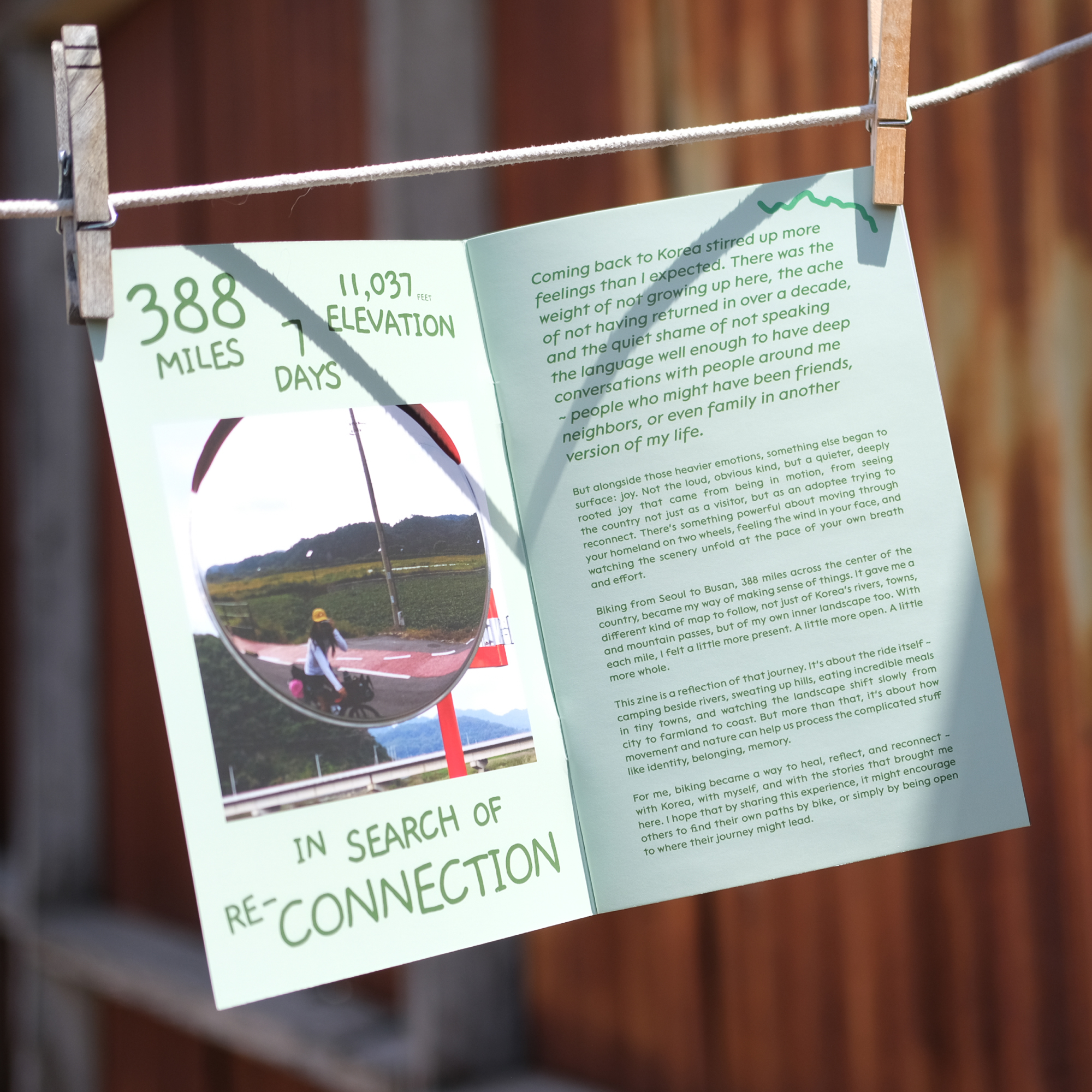

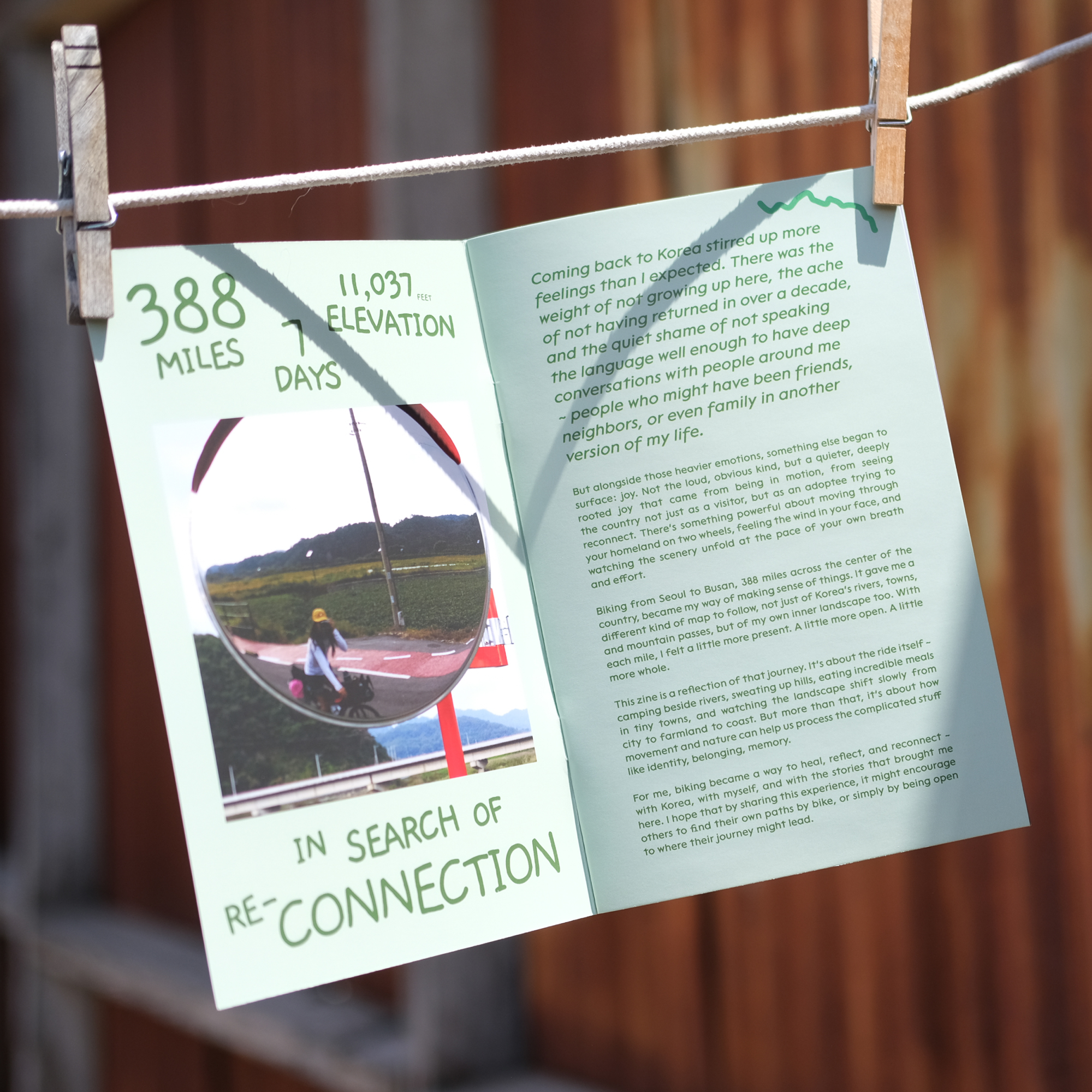

In Search of Re-Connection

Coming back to Korea stirred up more feelings than I expected. There was the weight of not growing up here, the ache of not having returned in over a decade, and the quiet shame of not speaking the language well enough to have deep conversations with people around me. People who might have been friends, neighbors, or even family in another version of my life.

But alongside those heavier emotions, something else began to surface: joy. Not the loud, obvious kind, but a quieter, deeply rooted joy that came from being in motion, from seeing the country not just as a visitor, but as an adoptee trying to reconnect. There’s something powerful about moving through your homeland on two wheels, feeling the wind in your face, and watching the scenery unfold at the pace of your own breath and effort.

Biking from Seoul to Busan, 388 miles across the center of the country, became my way of making sense of things. It gave me a different kind of map to follow, not just of Korea’s rivers, towns, and mountain passes, but of my own inner landscape too. With each mile, I felt a little more present. A little more open. A little more whole.

I created a zine as a reflection of that journey. It’s about the ride itself: camping beside rivers, sweating up hills, eating incredible meals in tiny towns, and watching the landscape shift slowly from city to farmland to coast. But more than that, it’s about how movement and nature can help us process complicated stuff like identity, belonging, and memory.

For me, biking became a way to heal, reflect, and reconnect with Korea, with myself, and with the stories that brought me here. I hope that by sharing this experience, it might encourage others to find their own paths by bike, or simply by being open to where their journey might lead.

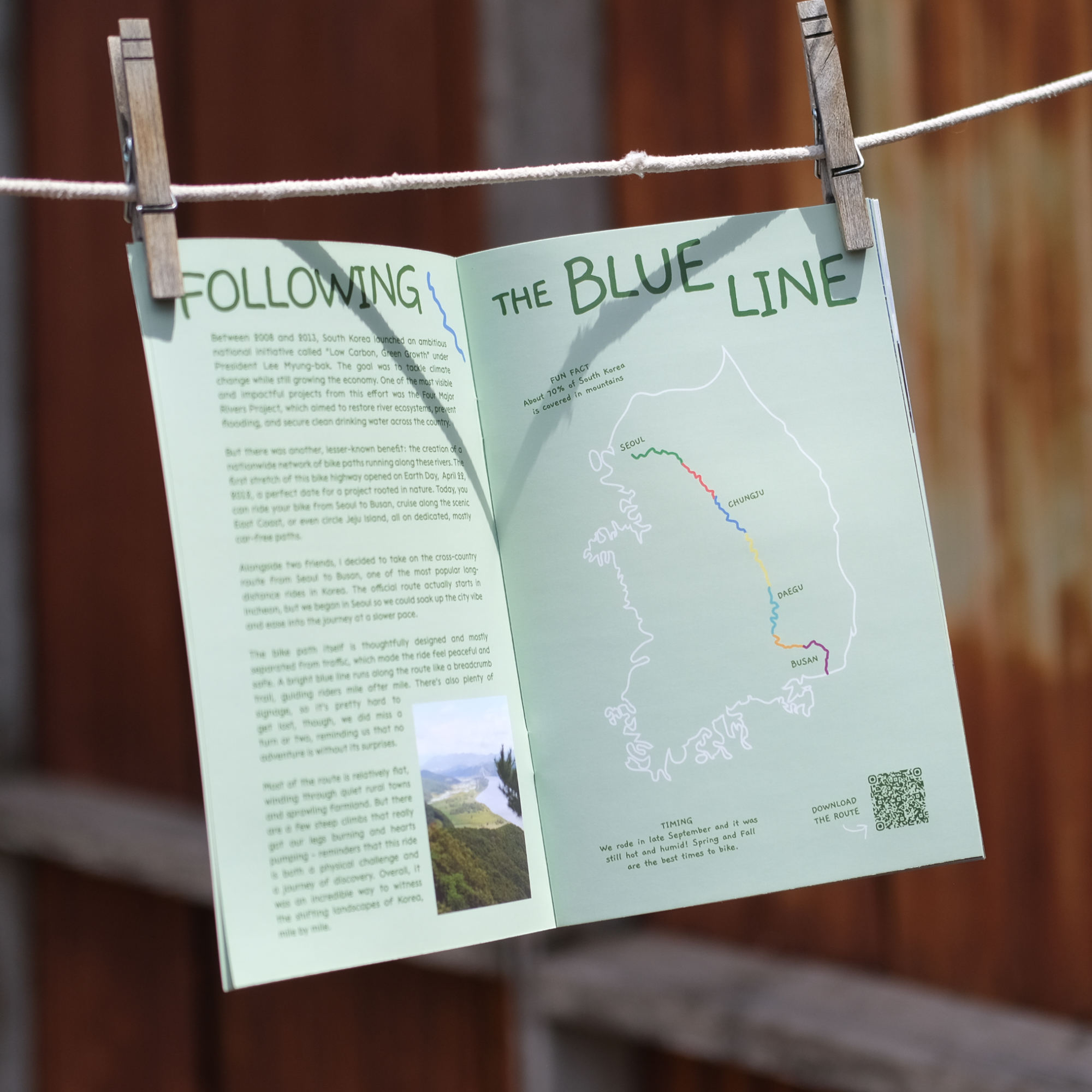

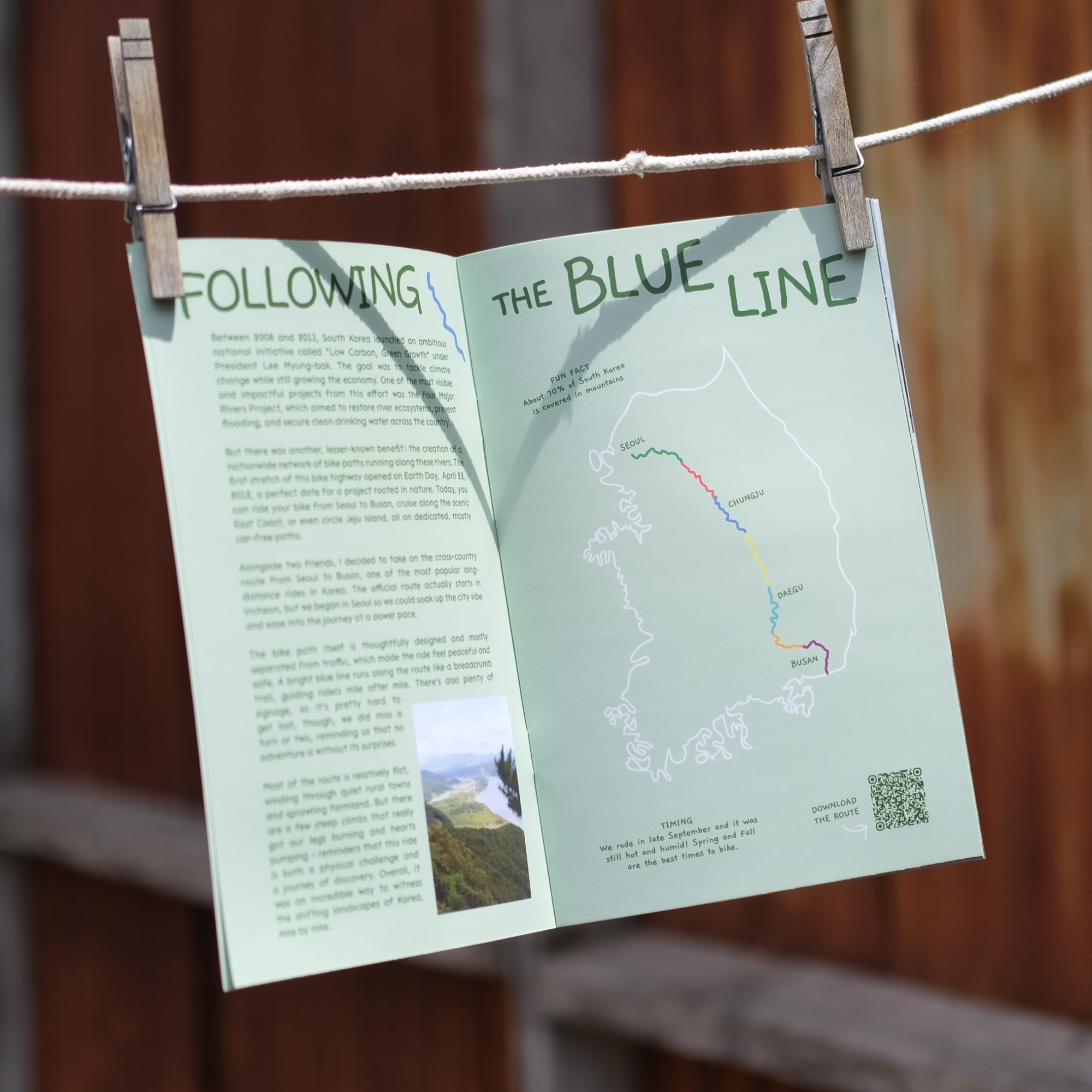

Following the Blue Line

Between 2008 and 2013, South Korea launched an ambitious national initiative called “Low Carbon, Green Growth” under President Lee Myung-bak. The goal was to tackle climate change while still growing the economy. One of the most visible and impactful projects from this effort was the Four Major Rivers Project, which aimed to restore river ecosystems, prevent flooding, and secure clean drinking water across the country.

But there was another, lesser-known benefit: the creation of a nationwide network of bike paths running along these rivers. The first stretch of this bike highway opened on Earth Day, April 22, 2012, a perfect date for a project rooted in nature. Today, you can ride your bike from Seoul to Busan, cruise along the scenic East Coast, or even circle Jeju Island, all on dedicated, mostly car-free paths.

Alongside two friends, I decided to take on the cross-country route from Seoul to Busan, one of the most popular long-distance rides in Korea. The official route actually starts in Incheon, but we began in Seoul so we could soak up the city vibe and ease into the journey at a slower pace.

The bike path itself is thoughtfully designed and mostly separated from traffic, which made the ride feel peaceful and safe. A bright blue line runs along the route like a breadcrumb trail, guiding riders mile after mile. There’s also plenty of signage, so it’s pretty hard to get lost, though we did miss a turn or two, reminding us that no adventure is without its surprises.

Most of the route is relatively flat, winding through quiet rural towns and sprawling farmland. But there are a few steep climbs that really got our legs burning and hearts pumping ~ reminders that this ride is both a physical challenge and a journey of discovery. Overall, it was an incredible way to witness the shifting landscapes of Korea, mile by mile.

Where We Slept

One of the things I appreciated most about biking from Seoul to Busan was how easy it was to find places to sleep, even without booking anything in advance. The ride felt open-ended and flexible, which matched the way I wanted to move through the country: slowly, with space to take it all in.

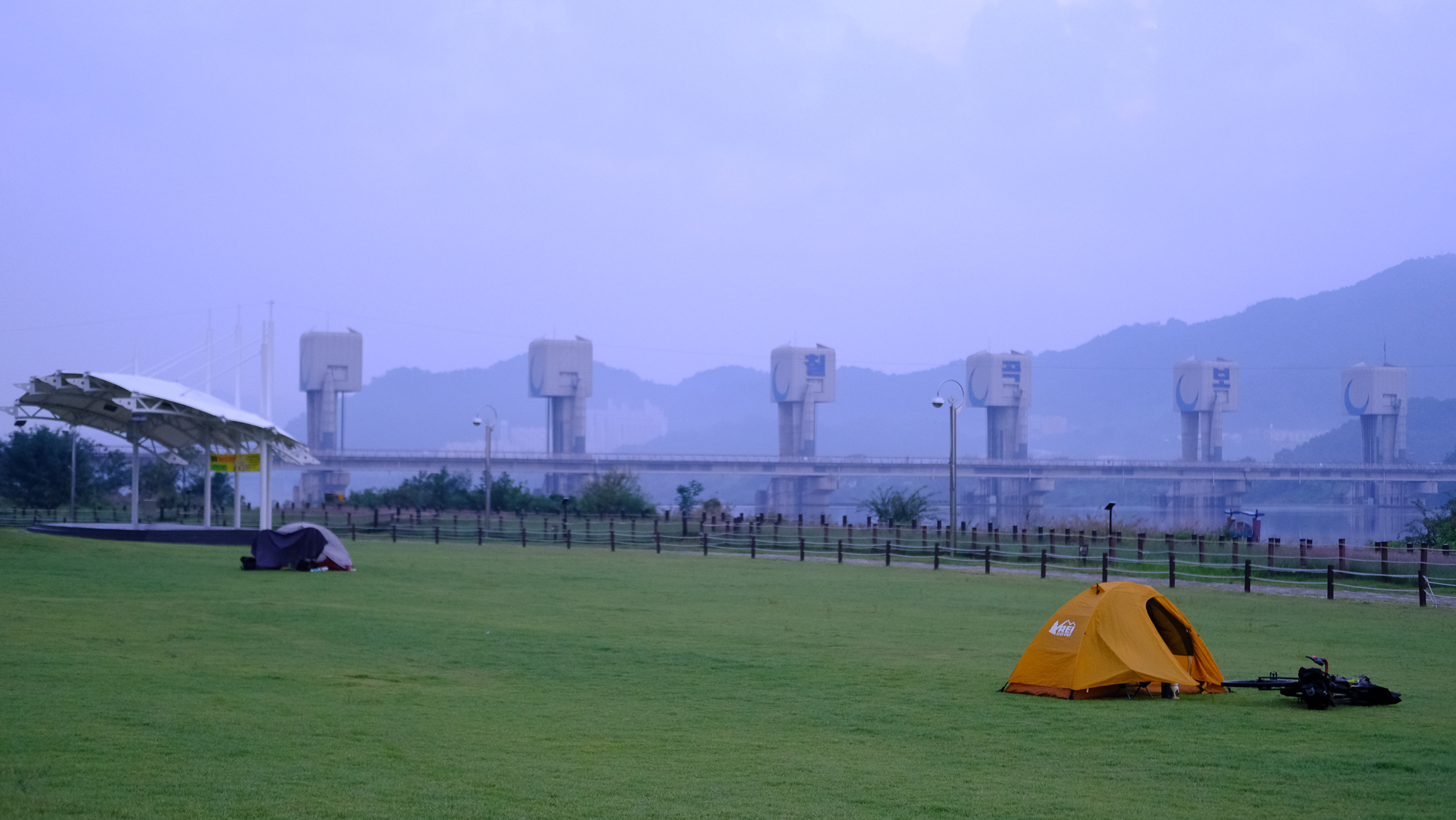

If you’re carrying a tent, camping is surprisingly simple. Many riverside parks and rest areas have flat, grassy spots perfect for pitching a tent. We camped right beside the water a few nights, which felt peaceful, quiet, and free. While wild camping isn’t always officially allowed, as long as you’re respectful and discreet (setting up after dark and packing up before sunrise), no one seemed to mind.

Sleeping outside here felt deeply grounding. As an adoptee visiting Korea as an adult, I initially felt like an outsider in what’s technically my homeland. But waking up in small-town parks, watching elders stretch or walk laps as the sun rose or set, felt soft, gentle, and unexpected. It wasn’t dramatic or overwhelming. It was a quiet kind of belonging, like I was allowed to be here, even welcomed in the everyday rhythms of life.

When we weren’t camping, we stayed in love motels, which turned out to be a quirky, affordable, and surprisingly great option. They’re not just for couples; travelers of all kinds use them. The rooms are clean, private, and budget-friendly (around ₩40,000 or ~$30–35 USD), often with fun extras like giant TVs, fancy bathtubs, or mood lighting. They’re usually easy to spot by the discreet tassels decorating the front of the building.

Mixing camping with motel stays made the trip feel spontaneous and flexible, with less pressure to plan every detail, leaving room for reflection and moments to simply feel as they came.

Group Tips: If you want two beds, they can be harder to find, especially in smaller towns. If you’re traveling with a group or during peak season, it is a good idea to book ahead.

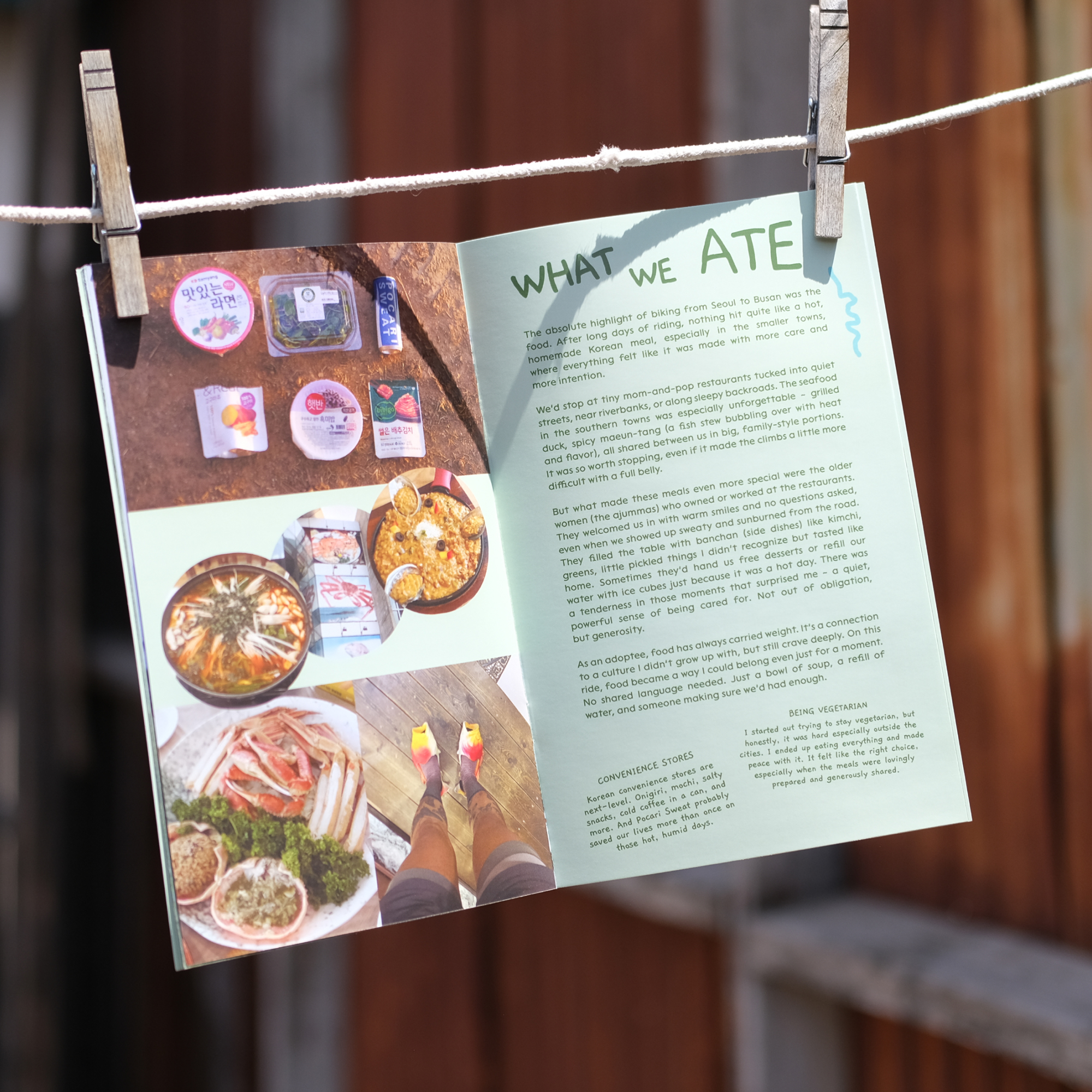

What We Ate

The absolute highlight of biking from Seoul to Busan was the food. After long days of riding, nothing hit quite like a hot, homemade Korean meal, especially in the smaller towns, where everything felt like it was made with more care and more intention.

We’d stop at tiny mom-and-pop restaurants tucked into quiet streets, near riverbanks, or along sleepy backroads. The seafood in the southern towns was especially unforgettable: grilled duck, spicy maeun-tang (a fish stew bubbling over with heat and flavor), all shared between us in big, family-style portions. It was so worth stopping, even if it made the climbs a little more difficult with a full belly.

But what made these meals even more special were the older women (the ajummas) who owned or worked at the restaurants. They welcomed us in with warm smiles and no questions asked, even when we showed up sweaty and sunburned from the road. They filled the table with banchan (side dishes) like kimchi, greens, and little pickled things I didn’t recognize but tasted like home. Sometimes they’d hand us free desserts or refill our water with ice cubes just because it was a hot day. There was a tenderness in those moments that surprised me; a quiet, powerful sense of being cared for. Not out of obligation, but generosity.

As an adoptee, food has always carried weight. It’s a connection to a culture I didn’t grow up with, but still crave deeply. On this ride, food became a way I could belong, even just for a moment. No shared language needed. Just a bowl of soup, a refill of water, and someone making sure we’d had enough.

Convenience Stores: Korean convenience stores are next-level. Onigiri, mochi, salty snacks, cold coffee in a can, and more. And Pocari Sweat probably saved our lives more than once on those hot, humid days.

Being Vegetarian: I started out trying to stay vegetarian, but honestly, it was hard especially outside the cities. I ended up eating everything and made peace with it. It felt like the right choice, especially when the meals were lovingly prepared and generously shared.

Thank You

Biking from Seoul to Busan was more than just a physical journey; it was a way to move through memory, belonging, and identity at my own pace.

Some days were hot and heavy, others light and full of laughter. But every mile taught me something: that healing can happen quietly, that connection doesn’t always require words, and that movement, literal and emotional, can open up space for understanding.

As an adoptee returning to Korea, this ride wasn’t about finding every answer. It was about letting myself be present in a place that has always felt both mine and not mine. And in that space in-between, I found softness in riverside campsites, in shared meals, in the smiles of strangers who welcomed us in without hesitation.

This zine is just a small piece of that experience, but I hope it reminds others, especially fellow adoptees, that your story, your way of returning, your pace… It’s all valid.

If this zine resonated with you, consider supporting BIPOC Adoptees, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to creating safe, inclusive spaces for adoptees of color. Their mission is to uplift BIPOC adoptees through community, storytelling, education, and care, while challenging the systemic erasure and neglect adoptees often experience. This zine was first shared at the 2nd Annual BIPOC Adoptees Conference in Portland, Oregon.

If you’d like to purchase the full zine, visit Long Distance Studio. Proceeds help cover production costs and support Molly’s upcoming fall bike tour in Korea along the East Coast and Jeju Island.